We should invest. We really should.

Compounding interest is called the eighth wonder of the world because of it’s tremendous and stealth power. A sum growing at 7% a year will double every 10 years. This means that the exponential growth of our savings into significant wealth is possible within the scale of our lifetimes. Which means that getting rich should not be all that difficult for those with access to capital and the market.

To invest intelligently is to treat your money as a bacteria plated on agar. It is to allow capital to sit unattended in an incubator and to divide and divide again and to grow from something small into something palpable and important and powerful.

Compound interest

Money left alone to grow will eventually become more economically productive than the person who earned it originally (which is a somewhat perverse, but useful fact to be aware of.)

But the question that follows from this fact is not so happy. If money alone, invested simply and intelligently can grow so powerfully, then why isn’t everybody rich?

And there are many answers to this question. among them…

We save too little.

We spend too much.

We invest too conservatively.

We pursue lottery like investments with low likelihoods of big jackpots.

But even if we do invest in a rational manner: the real reason for our almost inevitable eventual failure is this: we are hardwired to fail at investing.

We are chock full of impulses to do exactly the wrong thing at the wrong time.

It turns out that the traits that were useful to the survival of our ancestors, like quick decision-making, and intuition, and risk avoidance, and the paralyzing fear of losing wealth, all conspire to make us do exactly the wrong things at the wrong times when it comes to managing our own money.

And this study of this irrationality is an entire field within finance. This speciality is known as behavioral finance.

Although behavioral finance is quite interesting, I am not sure that I believe that studying behavioral finance has the power to really help investors avoid falling into the many behavioral traps of investing.

It seems to me that there remains a stubborn disconnect between the part of the brain that reads about behavioral finance,(System 2 in Daniel Kahneman’s vernacular) and the part of the brain that really influences most of our decisions, (system 1.)

An example that keeps on coming to mind of late is the ageless question within finance: “What is risk?”

There are many ways to answer this question. Among them:

Risk is Volatility.

It is certainly true that assets that move up and down rapidly and violently have more of a tendency to lose their value (and gain their value ) very quickly. But this definition treats upward price movements and downward price movements equivalently, when rapid movements upward are certainly not a measure of risk.

Risk is inadequate growth.

Although investing in an FDIC insured savings account has almost no risk of losing principal, The slow growth of a savings account makes it very unlikely that the saver will ever reach his or her financial goals. In fact it is likely the principal’s purchasing power will slowly be lost every year to inflation.

Risk is maximum drawdown.

Maximum drawdown measures the greatest percentage of the portfolio lost from any peak to any trough in its history.

So a portfolio that had lost a maximum of 50% of its value in one time period over the past 90 years would be seen as a more risky portfolio than one which had lost only 10% of its value over the same time period.

This is probably my favorite measure of risk. After all losing large percentages of money makes it very difficult to gain that money back in a timely fashion. So it erases years of compounding growth. Plus losing lots of money makes human investors like us more likely to make bad decisions like selling low and buying high.

Put simply, losing significant wealth is what most investors lie awake at night worrying about. It’s what we want to avoid.

But even this metric (my favorite) really misses the mark because it doesn’t capture risk as we humans really experience it. (More on that to follow.)

Risk is the likelihood of doing something stupid.

This is the risk that most of us should probably be paying the most attention to.

Doing stupid things and paying too much in fees/taxes are undoubtedly the commonest risks when it comes to investing.

This is part of the reason why I am so bullish on Betterment.

It is all too easy to overestimate one’s own discipline and to laugh at the mistakes that other investors are bound to make. But the fact is that arrogant investors are human too, and if we are convinced that we will not make stupid mistakes, then the most likely conclusion is that we are overconfident, and paradoxically more likely to make mistakes than others.

A service like Betterment allows you to save a good proportion of your money in a rational diversified manner for a pittance, and never check the stock market.

I have heard it claimed that Fidelity did a study of individual investors, and found the most successful investors in terms of total returns over a long time periods fell into two groups; those who had forgotten that they had retirement accounts, and those who had died.

This study, if true, certainly lends credence to John Bogle’s famous advice for investors: “don’t do something, just stand there!”

When it comes to making intelligent decisions about managing our own money, I think it’s quite likely that computers and algorithms will consistently do it better than people. They have different DNA.

But back to the central topic at hand. Why is there such a disconnect between measured risk in investing and the way that humans actually experience risk?

I believe it has to do with our inability to sense slow changes over long time periods, and our over sensitivity to small fast changes.

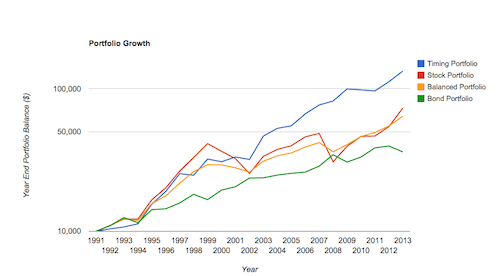

Take a look at this chart.

This compares the performance of a global equity momentum portfolio (in blue) with that of an all-stock portfolio, a 60:40 stock: bond portfolio, and an all bond portfolio.

Looking at this graph it is almost impossible not to be impressed by the performance of global equity momentum.

If you are like me then the first thing that jumped out at you was how impressively GEM outperformed everything else. And all else being equal we investors will always take as much performance as we can get.

But the thing that really impressed me about using a dual momentum strategy such as global equities momentum, was how impressively it navigated through the two major bear markets of the 2000’s.

Looking at that the Graph it is impossible not to come to the conclusion that global equities momentum is less risky than the other strategies. During the financial crises the portfolio moved seemlessly into short-term treasuries or T-bills (essentially zero risk assets). This timing mechanism allowed the dual momentum strategies to stop the bleeding while all of the other strategies continued to fall.

But here’s the problem with that conclusion. When we are looking at a graph such as this we are looking at years at a time. And we tend to fast-forward right to the end to see how it all turns out. (It is also easy to ignore the first 10 years where the momentum portfolio underperformed the all stock portfolio, and over some stretches even the bond portfolio.)

But as real-time investors this is not how we experience the market. The future is unknowable, and so each day that we are out performed by the market pains us. It worries us terribly that the downward trend will continue. And because of the way we experience changes in our own wealth, we will generally experience much more pain from losing a bit of money than we will experience joy from gaining a bit of money.

This means that if we lived in a world where every other day the market (somehow unpredictably) alternated in between gains of 1.1%, and losses of 1% (which in the end would mean that we would have a relatively smooth rise upwards of about 9% a year), we would experience this market as 102 trading days of severe pain, and 102 trading days of moderate joy. Our every day perception would be one of risk and hazard and we would likely be continually tempted to decrease the volatility of our portfolio in order to avoid the unpleasant feeling of loss.

In a sense the smooth ride upward would be experienced as a death by 1000 cuts, despite the fact that the sequence of returns would end up leading, one year later, to a 9% bigger portfolio. (and keep in mind that the volatility of the real market is much more violent, unpredictable and tied to real world confusion.)

The whole experience is irrational, but then so are we. We are hopelessly blind to the crucial wealth building slow upward movements of asset price and can only see them after-the-fact. Conversely we are exquisitely sensitive to the noise in the day to day up-and-down price movements (especially the down ones) that usually don’t really add up to anything.

We are attuned to the short-term and oblivious to the long-term. This is our common inheritance as human beings.

And unfortunately investment is a slow moving game sketched out on a canvas of the long term.

In the end my guess is that the ability to focus long-term events, and to willfully ignore short-term price movements, ends up being a rare and crucial quality in smart investors like Warren Buffett. I am not sure where this perspective comes from. Is it a stubborn belief in the soundness of their own strategy? Is it a personality type? It remains unclear.

Pruning trees? Why bother? I’m too busy managing forests.

Rare investors like Buffet are somehow able to ignore the 1000 cuts of underperformance over years and years and years, and to keep their focus on the slow, ineffable, upward movement of well chosen asset prices over time. And if that were as easy as it sounds we probably never would’ve learned Buffet’s name.

7 Responses to “Forest For The Trees”