Most of us are shrink wrapped in our own ideology. Some of us more so than others.

I’m certainly very, very, ideological.

I come from a long line of secular Jews. My great grandparents and grandparents fled countries where they weren’t welcome. They were underdogs. They stuck out like sore thumbs. They were beaten by Cossacks and literally threatened with genocide by cruel nationalist majorities.

And probably because of this heritage I was bathed from a young age in the ideology of liberalism. In the idea that the weak had to be protected from the strong. That justice was something to be fought for, never granted. That the powerful and wealthy, left unchecked, would always move to consolidate and protect their own entitlements to the detriment of the have-nots. And that rational laws and government could serve as a bulwark against this predation.

From a young age teachers told my parents that they were convinced I would become a lawyer or a judge. So obsessed was I with justice and fairness.

And obviously I’m painting myself in the best possible light here. (Another irrational bias.)

But that’s neither here nor there.

The point that I’m getting to is that most of us have strong biases. And we are unconciously searching for data points that reinforce our own preconceptions. Be they liberal, conservative, religious, secular, artistic, or rebellious.

It’s this instinct that makes us more likely to group together with people of like mind. To irrationally become tribal and blind to reality. To close ourselves off to new ways of looking at the world.

But sometimes we become involved in debates. And we talk to those who just think oppositely from us. And it’s as if we speak two different languages.

How then can we resolve these disputes? How can we rationally see past our own ideological lenses?

Well one way that makes sense to me, is to look at the ability of varying hypotheses to predict outcomes.

A (convenient) example:

The 2012 presidential election.

Leading up to the election there was a vast amount of polling data. Polls of all stripes showed a small but persistent edge to Obama in most of the battle ground states.

Sabermetrically inclined statisticians like Nate Silver aggregated all of the available data and weighted it based on prior poll accuracy, and sample size, and came to the conclusion that Obama was going to win with almost 80% certainty.

But if you were to tune into FOXNews, and listen to Karl Rove, or if you were to read the Washington Examiner, and Michael Barone, you would’ve been presented with quite a different model. One which basically said that all of the polling was misweighted and that mitt Romney was going to win the election by a healthy margin.

And before the election two reasonably intelligent partisans could argue until they were blue in the face about whose model was right. And neither side would budge an inch.

But then there was an election. There was a result. There was reality.

And the obvious conclusion was that one model was more correct, and one model was less correct.

Parenthetically, one of the most enjoyable parts of election evening (for this vindictive liberal) was watching Karl Rove meltdown live on FOXnews as he argued that reality was conspiring against him.

And the reason why this is important, is that there’s going to be another election. And one model was more predictive than the other model. And so, if the next Mitt Romney goes out and his pollsters skew his polls towards an inaccurately nostalgic vision of the electorate, then his side will be doomed to repeat the same mistakes over and over again. And they won’t progress.

There it is; prediction, separating the wheat from the chaff.

How about a nonpolitical conflict?

How about the age old clash of creationism versus the theory of evolution? This is a particularly frustrating argument to get into from either perspective, because the assumptions are just so different for each of the parties. Communication is next to impossible.

And let’s face it, on some level it is a matter of faith. Most of us have not directly experienced evolution, or creation. But this debate has been going on for hundreds of years now.

And the scoreboard could not be clearer. The theory of evolution has been useful. It has given us endless insight into the behavior of biological systems. It has given us life-saving breakthroughs into areas such as chemotherapy resistance, and antibiotic resistance. And robust evidence of genetic evolution was predicted and has been proven to exist in our nuclei, enscripted in the Nucleotide pairs that encode the genes that no one even knew existed at the time Darwin conceived of the theory of evolution.

What useful discoveries has The theory of creation given us? What technology has been developed? What prediction has been foretold? (Note: I am not arguing that the story of creation has no value, here, just no predictive value)

What biblical technology, for that matter, do creationists use to broadcast their theory over the airwaves?

Flagship station of the Creationist Broadcasting Network?

There it is; prediction, separating the useful from the dogmatic.

A final example, and one that you can both talk about at the dinner table, and that is actually relevant to this blog.

The debate over whether active or passive investing is a better strategy has been going on since John Bogle invented the first index fund.

And interestingly before Bogle invented the first index fund, he wrote an award winning academic article arguing that active investing was superior.

And convincing arguments can be made on either side before there is data.

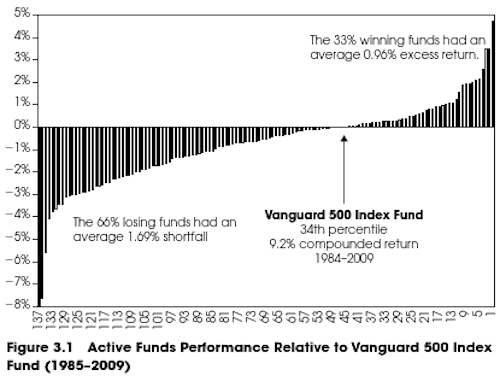

But the debate is old enough now. The data is in. And it almost always looks like this.

If you invest passively you will beat 60 to 70% of your risk matched active competition. And even if you’re lucky enough to bet on an active strategy and win relative to the passive competition, you will not be paid commensurate with the risk you took of losing, and you will be more likely to lose in the future.

So passive investors have not only made a prediction, they have bet on it! And year in and year out they have won.

(And won in proportion to the additional cost that active investing incurred.)

So there you have it: prediction, separating the fool from his money.

As an aside, I do realize that all three arguments support my own baseline prejudices.

And I know that there are plenty of examples that do not shine so favorably upon my perspective. (That I chose these is merely evidence of my own myopia.)

Feel free then, to share with me some examples of where my side was wrong (The inflation of the 70s comes to mind vis-à-vis Keynesianism), that I lack the intellectual honesty to see for myself.

16 Responses to “Fortune Telling”