This whole series of posts started with a Warren Buffett quote, so you knew I was going to get back here. Back to value investing.

But before I dive in, once again, to the value anomaly, a confession.

I have some serious reservations about including value investing under the umbrella of strategies to be pursued in order to cowardly avoid losing in the stock market.

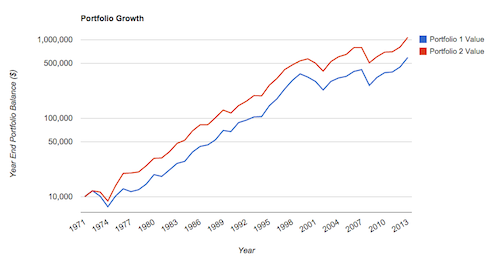

As an example let’s take a look at the retrospective performance of large-cap value stocks versus all large-cap stocks (large cap blend).

Blend=Blue, Value=Red

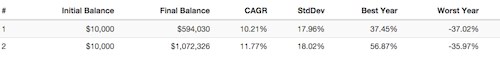

And what do we observe? we see that large cap value stocks compounded at a rate of 11.77% versus a rate of 10.21% for the large cap blend stocks. So $10,000 invested in 1971 ended up growing into $1,072,000 with the value strategy versus only $594,000 for the blend strategy.

But the volatility was almost identical, with a standard deviation of 17.96% for the blend strategy versus 18.02% for the value strategy.

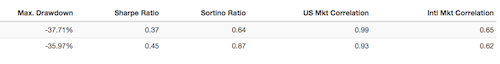

Furthermore the maximum drawdowns were also almost identical at 37.71% for the blend strategy and 35.97% for the value strategy.

So it’s easy to make the case that a value approach (before fees) leads to outsized compounding gains, but it’s much tougher to make the case that these gains are brought about by a diminished down side as opposed to an augmented upside.

So why include value investing in this series on cowardly (in a good way) investing approaches?

Well, for a couple of reasons.

The first (and the least defensible) is that value investing has historically been one of the most successful investing approaches, no matter how you slice it.

If you were to name 5 or 10 great investors, at least half of them would likely be value investors.

Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, Carl Icahn, Bill Ackman, Joel Greenblatt, David Einhorn, Seth Klarman….they are all value investors.

But more importantly, value investing at its core, is all about pursuing a “margin of safety.” By simply buying cheap stocks the value investor avoids taking on the risk of purchasing overpriced assets, which by definition have a longer way to fall during bad times.

Furthermore when the market gets frothy, and all stocks are priced above their sensible value, a true value investor will usually have a large cash position to avoid the coming devastation. For a value investor wants only to purchase investments at a discount. So when everything is expensive the value investor would just assume pick up his ball and go home, rather than play on in a risky game.

But I think the best way to pigeonhole value investing in with this ideal of cowardly investing, is with the concept of “net-net” companies.

For a more accurate definition of net–net investments, see here, but a simplified definition would be to take all of the cash and asset liquidation value in a corporation and subtract the liabilities to get the net current asset value of the corporation. Then compare that net current asset value to the current value of all the stock in the company.

(So if the stock in question were a lemonade stand, you would take all of the cash, and the cash value at liquidation for the lemons, sugar, stand, squeezer, etc..then subtract the debts owed by the company to get the “net current asset value,” you would then compare that number to the value of all of the stock in the company, and if the net current asset value was larger, you would have a “net-net.”

So if the net current asset value is more than the net value of all of the stock in the company, then you’re able to buy the entire company for less than its liquidation value.

In other words, if the company were to file for bankruptcy and have all of its assets sold at liquidation, then the stockholders would end up with more cash than the stated value of their stock before bankruptcy. (Which wouldn’t suck at all.)

And this idea of buying a company at a deep discount is really the central core of value investing. The reasoning is obvious. What better downside protection could an investor hope to have?

When we consider investing in a company it is always smart to think about worst-case scenarios. And in the case of a net net company, the worst case scenario, bankruptcy, leads to an appreciation of the investors capital!

But as usual there are disclaimers galore…

- Though I tilt my buy-and-hold portfolio towards value index funds, I am in no way a value investor, and wouldn’t recognize a net – net if it hit me in the face.

- The source of the value premium is controversial, and some efficient market true believers claim that it is just another risk premium and that value companies are more susceptible to shocks during economic downturns.

- By all accounts true Graham net-nets are tough to find these days.

- While some value investors do have track records of returns out of proportion to risk, this is often because they hold more cash than the average investor and deploy their cash when opportunities abound. (In other words they are skilled market timers, which ain’t easy.)

- There is lots of evidence that trying to beat the market with good market timing is a fool’s errand for the vast majority of investors.

So maybe covering value investing in this series was a bit of a misdirection. But I’d like to think that the best value investors, like the best investors everywhere, make their hay by avoiding large and destructive losses of capital. In other words, they are excellent cowards.

What say you? Comments welcome…