There is something surprisingly useful about broadcasting your own assumptions to other people

There is this concept called “what you see is all there is,” (WYSIATI) discussed extensively in Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast And Slow.

And the point of WYSIATI is that our minds (particularly our intuitive “system”) are extremely biased towards narrative. So if we get a couple of facts we use our amazing powers of association to construct a linear story from the limited data.

What we don’t do is take into account all of the facts that are not at our disposal, or the quality of the facts that are. And this ends up being a frequent source of misjudgment. It is an extremely non-statistical way of thinking, (that we are all quite prone to.)

Which is where this “broadcasting your own assumptions” phenomenon comes in.

When I wrote my recent piece about the role of bonds in a portfolio, my feeling was that I was describing a basic plain-vanilla truth held by most people interested in portfolio theory.

But I found that I was wrong. Which makes me think that my own unconscious patterns of thinking end up being the ultimate example of WYSIATI.

The limited data in this case, was my own filtered perception of the world which is continually and subconsciously molded and engineered to mesh with my own attitudes and biases.

And in some of the polite clashes of disagreement present in the comments section of that particular thread, a central question occurred to me, that at least in my own mind seemed to be at the heart of most of the disagreement.

What is risk?

More particularly, when investing how do we define risk?

Which seems as good of a subject is any, so let’s take a crack at it.

Risk is standard deviation.

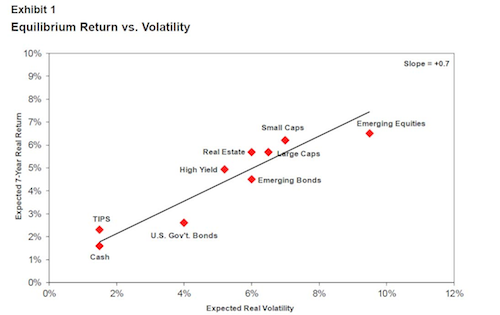

I believe that standard deviation, or volatility is the most classic definition of risk when looking at an asset.

The idea here is that the risk of an investment or of a portfolio of investments is represented by the movement up-and-down of the price of that investment.

And this definition ends up being a pretty useful one. It matches up very nicely with our own intuitive sense of risk.

If we think of small companies and big companies we would naturally expect the stock price of small companies to move up and down more violently because they are more susceptible to price shocks and environmental factors than large companies.(Small companies go bankrupt a lot more often than large companies, and also grow much faster when something positive happens to them.)

Or to take another example. Consider countries at varying stages of development. Frontier markets (think Nigeria), emerging markets (think China), and developed markets (think Germany). During times of financial stress we expect the developed markets to do better than the emerging markets and the emerging markets to do better than the frontier markets. Conversely we expect much more rapid rates of growth during good times from the less developed markets.

And when considering the risk of bonds versus stocks, particularly treasuries versus stocks, it is quite intuitive that borrowing money from a company is not as secure as borrowing money from the U.S. Treasury (which in fact prints the world’s reserve currency.)

Volatility is risk. And Risk leads to return…

And this intuition is what we see when we look at the numbers. The larger the company, the more developed the country, and the more bond like the investment the less volatile its price will be, in general.

One criticism of volatility as a measure of risk is that it treats upward movements of price and downward movements of price identically. And although upward price movement is clearly not risk, it turns out that when you measure downward volatility it ends up measuring the same thing as simple volatility.

Risk is losing all of your money.

This is a good definition of risk, no?

The real life risk of investing your retirement money is losing it all and spending your last days destitute and broken. (William Bernstein often evokes eating cat food under a bridge to describe this sad outcome.)

And when we think about this type of risk, it is inextricably linked to volatility.

In terms of losing capital, a portfolio of 100% T-bills is much less risky than a portfolio of 100% long-term treasury bonds which is less risky than a portfolio of 100% developed countries stocks, which is less risky than a portfolio of 100% emerging markets stock, Which is less risky than a portfolio of 100% frontier markets stocks.

As your portfolio shifts towards more volatile assets, it’s risk of total loss with financial collapse goes up. (This is why leveraged investors sometimes kill themselves when financial bubbles burst. They lose everything…)

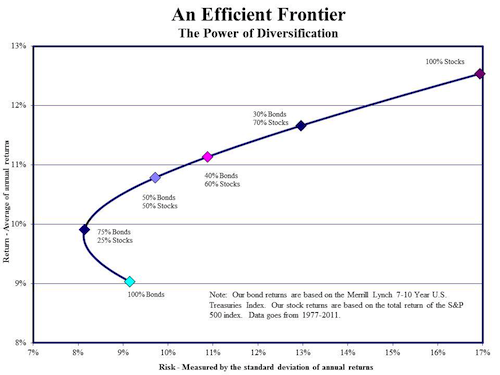

(This is not to say you should not own volatile assets. When mixing different volatile assets without perfect correlations you often paradoxically decrease the entire portfolio’s volatility (risk) at the same time you increase its returns. This is the so-called “diversification benefit”.)

This is why, in my view, the less you can afford to risk your capital, the greater the percentage you should own of stable assets like bonds in your portfolio.

One need simply imagine A portfolio of 100% stocks, when compared to a portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds during our most recent financial collapse.

When the 100% stock portfolio was faced with a 50% drop in the value of The stock market, it lost on average 50% of its value. Assuming bonds did not go up or down at the time of the collapse (they usually go up) The 50/50 portfolio would’ve lost only 25% of its value.

But this is not the only risk possible when investing…

Risk is not having enough money in retirement because your investments do not make enough money.

Taking all of your retirement money and putting it under your mattress is actually a very risky thing to do (even if you have 100% guarantee that your house will never be robbed or burn down etc.) This is because your money, instead of compounding, is continually losing buying power to inflation. It is shrinking in value. This makes it very difficult to save enough money for retirement.

Similarly, if you created an entire portfolio of 100% short-term treasuries, your risk of losing all of your money is nearly zero, but your risk of not having enough money during retirement is substantial.

This is why even the most conservative investors should own some equity in their portfolios.

(Another reason is that paradoxically owning somewhere between five and 10% equities in your portfolio actually decreases the volatility ((and risk)) of your entire portfolio.)

Adding risk can decrease risk…..

Risk is losing money to inflation.

When it comes to inflation, cash is more risky than bonds which are more risky than equities and real estate.

So in this definition of risk, volatility is inversely related to risk!

And there are many more risks that I am not mentioning. (Please add yours to the comments section.)

But the point is that if your definition of risk as an individual will very much be determined by your own economic situation.

If you are a young worker trying to save for your retirement 30 years down the line, then a bond only portfolio is incredibly risky in terms of you not reaching your goal of a secure retirement.

Conversely if you are a retiree without much Social Security income and all of your portfolio invested in a 401(k), who is counting on withdrawing 4% of your initial portfolio value, adjusted for inflation, going forward, then an 80 or 90% stock portfolio is very risky in terms of you losing a big chunk of your portfolio, and running out of money.

Not to be a damned relativist. But I have to conclude that risk is very much in the eye of the beholder.

(I still hold that your bond percentage should be determined solely your risk tolerance. Defining risk is entirely up to you though.)

How would you define investment risk?

3 Responses to “Out On a Limb”