The most interesting man in the world is not a B rate Hollywood actor with a Hemingway knock off beard.

He’s not flanked at all times by bikini-clad swimsuit models.

He’s not paid to peddle south of the border malt beverages, or for his propensity to pronounce all words as one might utter “Corinthian leather.”

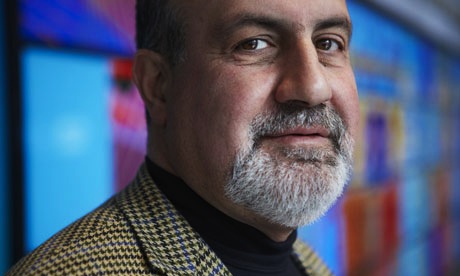

He is instead a Lebanese immigrant. He’s an Orthodox Christian. And he’s a former options trader.

He’s a polyglot and a polymath and an autodidact.

His style is muscular and sometimes even a little bit bullying.

His writing is often tangential and nonlinear and his books are not the sorts of things that one could easily outline.

But he is the most interesting man in the world because he possesses one of the rarest commodities of all: original thought.

I am speaking of Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who’s most recent book Anti-Fragile I just finished reading.

Interested?

This is a wonderful book that has changed the way that I look at the world.

And the whole book is really about one key insight. To paraphrase his insight it is this.

- It is impossible to predict large random events, or so-called black swans. (Though black swans are both inevitable and powerful agents of change.)

- It is however possible to recognize a subject’s sensitivity to randomness.

- As an example, a delicate blown glass bowl perched atop a high table can only be harmed by randomness. (Imagine randomness as a four-year-old playing catch in the same room as the glass bowl, or an earthquake, or a fire…) This sensitivity to randomness is defined as “fragility.”

- It is also possible to recognize a subject’s lack of sensitivity to randomness. (Think of a large rock on solid ground.) This quality is “robustness.”

- But the opposite of “Fragility”is not “robustness,” it is “anti-fragility” or that which benefits from randomness.

- An example of “anti-fragility” might be a biological species. This is because small random errors in the genomes of its individual members allow for the species to continually change and adapt to its environment, and in so doing to survive and to become ever stronger.

Which all sounds a bit abstract. Which is probably why the book clocks in at 426 pages.These pages are spent wondering here and there and assiduously tying the central concept to many real world practical applications. Like…

- How to structure a political systems to make them less fragile (he argues for small and decentralized systems.)

- How to mix low risk low reward investment strategies with high risk high reward strategies to create an investment strategy that achieves moderate rewards with less exposure to risk. (Barbelling.)

- How to incorporate small amounts of randomness into our habits in order to make ourselves more robust.

- How to avoid the iatrogenic effects of medicine. (Avoid medicines for small problems but use them for big ones.)

- How to differentiate between the value of old wisdom versus new knowledge. (Old concepts are worthy of respect, and new ideas are worthy of suspicion. This is because time is a randomness delivery device, so anything old must at least be robust if not anti-fragile, not true of new ideas which have not stood the test of time.)

And it’s truly a fascinating book which both entertains and persuades.

Which is not to say that I agree with Taleb all of the time. There’s much to disagree with, and there are easy logical inconsistencies to pick apart. (As an example he argues that there should be a cap on how large companies can become to avoid the “too big to fail/bailout” problem. But this prescription is quite inconsistent with his almost libertarian affinity for a small decentralized government. After all who enforces this proposed cap if not a government which is bigger than the largest corporations?)

But what I love most about Taleb’s insight is that his philosophy is quite actionable.

This philosophy is a prescription to focus our attention on that which matters, and to ignore that which does not.

As an example, since predicting the future in complex systems like the economy and the political system, is an exercise in futility, we can derive two lessons.

- It is a waste of time to base tactical decisions on our own predictions of the future.

- We should almost always ignore those who claim the ability to predict the future in such systems.

Furthermore since fragility, robustness, and anti-fragility are recognizable a priori (although the future is not) we should focus our attention on making the things that we care about less fragile. Individually we can do this by…

- Avoiding debt and saving more of our money, (which gives us options)

- Living in a more efficient, traditional manner (walk more, drive less, do our own lifting…)

- Eliminating the unnecessary from our lives (via negativa), rather than constantly adding complexity to them.

Undoubtedly some of Taleb’s appeal here is simple confirmation bias on my part. After all the lessons of anti-fragility (avoid debt, avoid overspecialization, avoid physical weakness,conserve the environment) are very much one-of-a-kind with the ethos of Mustachianism.

But it is quite reassuring that the world’s most interesting man reached these conclusions based on the mathematical concepts of convexity and concavity, the applications of risk management, and the wisdom of the ancients.

After all I’m just a guy who was searching for happiness in the blogosphere, and somehow we ended up coming to some pretty similar conclusions….

5 Responses to “The Most Interesting Man In The World”