My interest in early retirement is a recent development. (Further proof that the new convert is always the most fervent.)

So I sometimes wonder what I would have done differently had I had this philosophy when I first finished my electrophysiology fellowship and started my career.

From my current vantage point I can see that I certainly made a lot of mistakes.

I bought new cars for my wife and me with car loans. (And in essence became a generous issuer of compounding interest to a bank.)

I rented an unnecessarily expensive apartment to live in for our first year.

I then bought more house than was strictly necessary.

I bought $60 bottles of wine that I didn’t really like any more than $15 bottles of wine.

But do I regret any of it? Not really.

If I’d been more naturally frugal, of course, I now would be further along towards my goal of financial independence. But at what cost?

You see, my whole life, I had never really had much spending money.

To be sure I was exceedingly rich where it counted. My parents were both well-educated. I was sent to exclusive private schools on scholarship. I was allowed to pursue many interests such as baseball, singing, and art.

I was never hungry and never cold.

I never worried about my family’s finances.

But my inner baby was certainly always curious to know what it would feel like to have money to burn.

I wanted some more spending money, waaaahhhhh

So when my income shot up by about 300%, it really was time for a shopping spree.

And I had the incredible opportunity to experience that most of what I bought did not really bring me very much additional happiness.

Which was an important insight. But not a unique one.

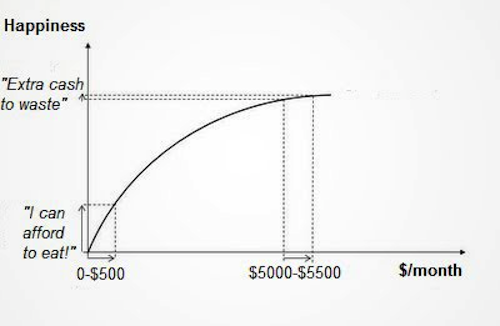

Economists call this concept the marginal utility of wealth.

And what it basically tells us is that once our basic needs are met, additional wealth, while it does provide additional benefit, provides ever diminishing additional amounts of benefit.

On a graph it would look something like this.

Which makes sense on an intuitive level, right?

If you’re parched, a glass of water is invaluable.

But after you have finished a glass of water how much is the second glass of water worth?

Less.

And the same is true of salary. Each dollar earned up to a point undoubtedly provides big-time gains in happiness. With the first dollar earned each day you can buy some canned food to tame the hunger pains in your belly. With the first $10 a day you can buy three square meals a day. With the next $20 a day you can rent a roof over your head with heated running water and a stove to cook on. And so on, until all of your basic needs, and maybe a few meaningful diversions are affordable.

But then like the second glass of water, the utility of wealth starts leveling off.

And once you have experienced this feeling of diminishing returns, you will really have one of two choices.

A. You can either try your hardest to make ever more money, to continue get ever smaller gains of additional happiness. (Probably at the cost of more risk, more effort, or more stress)

Or

B. You can start to focus on non monetary goals that actually bring you more happiness. Like spending time with your loved ones. Or pursuing something that you’re passionate about. Or being creative. Or helping others.

And in my experience pursuing financial independence is a tremendous way to effortlessly shift away from a model of ever diminishing returns towards one of ever compounding returns.

Living on much less than your take home salary means that you will have a lot of reserves. (And I’m not even talking about your savings.)

Imagine how different it is to hear that you’re getting a 25% pay cut if you’re living on 50% of your salary versus living on 100% of your salary. You certainly wouldn’t be happy. But you also probably wouldn’t feel an existential threat. (The kind of thing that can really take away from your happiness.)

And this freedom from the threat of unhappiness is truly addition by subtraction. Can a sports car really be expected to bring you as much in return?

And I think there are many more lessons that we can learn from the concept of the marginal utility of wealth.

1. Wealth and happiness are strongly correlated up to a point. But not past a certain point.

2. The path to happiness is shorter by diminishing your needs (spending) then by increasing your means (salary.) This is because you are giving up diminishing rewards, in exchange for compounding rewards.

3. Progressive taxation is intuitively fairer then flat or regressive taxation. Taxing an additional 5% of a poor man’s salary costs much more of his happiness than taxing an additional 5% of a rich man’s salary costs of his (I.e. my) happiness.

4. Working is the best way to attain freedom from poverty.

5. But once you’re freed yourself from poverty, saving is the best way to attain freedom from the need to work. (and by extension happiness?)

6. The happiest countries are not necessarily the richest countries. Here’s a nice little article on that. (The Moldova angle was a shocker. There is a Moldovan woman who I work with who is truly delightful and happy!)

7. At some point it becomes much more important for you to protect your investment wealth from losses, then it does to use your wealth to chase further wealth. (It’s a risk/benefit thing.)

But maybe if you’re starting a new career, and you really want to spend some dough, it’s the right thing to do.

My only advice for someone like the slightly younger me, would be to pay attention to how much happiness you’re gaining with your additional spending and try to identify the point at which your returns are diminishing.

Paying attention to reality is usually a pretty wise thing to do.

2 Responses to “Utility Bills”