Warning: this will not be a particularly well researched or philosophical post.

I’ve read my fair share on the subject I’m about talk about, but I’m certainly no expert.

The reason I’m writing this post is just to communicate the simple model that I have in my head when I think and talk about bonds.

The model may be right, and it may be wrong, but I would hold it’s important to have a blueprint when you construct something. And each feature of your blueprint must have a well-defined pre-specified function. Otherwise what you’re constructing is liable end up being a pile of rubble with no logic or utility.

(You should see the blueprints)

In this clunky metaphor the thing that we are building is a house, and the final construction will require many different parts A roof and windows, finish carpentry and cabinets, sheet rock and framing, sewer pipes and water pipes, Electric boxes and conduits and outlets…. You get the idea. It requires a diverse collection of materials.

And the house, of course, represents an investment portfolio.

But before we can pick out the glamorous parts; the flooring, or curtains, or solar panels, or light fixtures, or skylights, or cabinetry, we must start by digging a hole and laying the foundation. And the foundation of our house (Portfolio) is bonds.

What is a bond?

A bond is simply a loan or an IOU.

An easy example of a bond from every day life is a mortgage. The bondholder is the bank. And the issuer (Or debtor) is the person borrowing money to buy a house.

The bond is a contract representing items that the two sides agree on including a term (The length of the loan), and an interest rate (Or coupon) that will be paid over the life of the loan.

What types of bonds are there?

There are many types of securitized bonds that you can invest in.

There are government-backed bonds (or T-bills, treasury notes, or treasury bonds)

There are government-backed bonds whose interest rates are tied to inflation. (TIPS and I Bonds)

(In general US government backed bonds are felt to represent no risk of default.)

There are company backed bonds (or corporate bonds.)

There are company backed bonds from companies with a very low likelihood of defaulting on their commitments (investment-grade corporate bonds.)

And there are company backed bonds from companies who represent a higher risk to default. (Junk or high-yield bonds)

There are even bonds issued to people with limited assets, no collateral and a high-risk of default from other people, with a middleman taking a high fee off the top of the coupon. (P2P Bonds like lending club and prosper.)

I organized this first grouping of bonds based on credit risk. From the treasuries at the top to the P2P loans at the bottom these different classes of bonds represent successively increasing levels of credit risk.

Credit risk is the risk of losing your money when the bond issuer is unable to pay you back, as in the case of bankruptcy or default.

The more credit risk that is taken on, the higher the bondholders coupon should be.(Otherwise no one would ever lend money to high-risk borrowers.)

But bonds can also be organized by their terms.

Short-term bonds are for three years or less.

Medium term treasuries are from 3 to 10 years.

And long term treasuries are for 10 years or more.

In general the longer the term of the bond the higher the coupon should be (though this is subject to supply and demand in the marketplace.)

Why do long-term bonds pay higher coupons?

Before we answer this we must talk about the interaction of interest rates and bonds.

And before we get there we must talk about what the bond issuer is paying for with his coupon I when he borrows money from the bondholder.

He is paying for the inconvenience of delayed gratification (not spending his money.)

He is paying for the risk of his own default (the aforementioned credit risk)

He is paying for the risk of inflation (inflation risk.)

This is because as time goes on and inflation rises , the buying power of the coupon becomes less and less valuable. (Would you rather spend a quarter in 1960 or 2014?) And obviously the longer the term of the bond the more inflation risk there is as prices tend to go up.

And finally he is paying for interest rate risk.*

Coupons are naturally tied to current interest rates. This is because no one would ever borrow money at a rate less than the current interest rate that they could get from a risk-free asset like a FDIC insured bank account.

Now imagine a rising interest-rate environment. On day one an investor buys a 10 year treasury bond with a coupon of 3% at a current interest rate of 2%.

On day two interest rates rise to 3%.

Investors will now demand an extra percent on the coupon for 10 year treasuries. So on day 2, 10 year treasuries are now bid up to a coupon of 4%.

So how much is our investors 10 year treasury worth on day two?

If our investor wants to sell his treasury to another investor he will have to lower the price below the amount of the bond itself. This is in order to compensate the buyer for the coupon payments that he will not be recieving from the current issue of bonds for the next 10 years. So our investor will have to sell his 10 year treasury for about 90% of its original value. In other words, his treasury lost 10% of its value in one day. (In general if you multiply the term of the bond times the instantaneous change in interest rates you will get the percentage of value lost. (so a 10 year duration bond times one percentage point of interest equals 10% value lost.)

So the value of bonds, are inversely proportional to interest rates and this effect is stronger the longer the term of the bond.

Which (again) is why long-term bonds generally pay higher coupons than short-term bonds. The long-term bondholder is taking on inconvenience, interest-rate risk and inflation risk in addition to credit risk.

Why include bonds in your portfolio?

The long-term expected returns of stocks are almost always higher than the long-term expected returns of bonds. This means that every time we increase the amount of bonds in our portfolio we are expecting less growth of our portfolio. So whats the point of investing in bonds at all?

Which brings us back to our original metaphor.

Like a House rests on foundation, everything else in your portfolio rests on your bonds.

While stocks are zigzagging up-and-down on an overall skyward trajectory, Bonds are boringly marching upward slowly by the rate of their coupons.

And the shorter the duration and the lower the credit risk of the bond the less upward and more stable the slow march is.

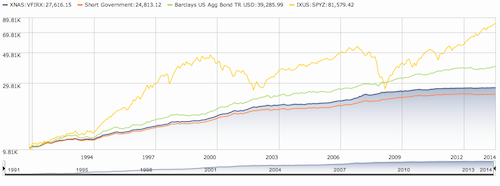

Blue= Short Term Treasuries, Green = Medium Term Total Bond Market, Yellow = S&P500

So the less your portfolio can afford to lose (or you the investor can stomach losing) the more bonds of less credit risk and shorter duration you should have in your portfolio.

So retirees who are constantly withdrawing funds will want a big foundation and a house somewhat like a bunker.

While a young and ambitious investor at the start of his career might want a less bulky foundation in order to erect a faster rising skyscraper.

Clearly built by young accumulator

And you will note that the one factor not mentioned in this calculation is the current interest rate. In low interest rate environments your bonds will make less (while your equities may well make more…) But the take home is….

The main determinant of your percentage of bonds should be your risk tolerance.

Compared to stocks, your bonds will contribute less to your wealth, but they will also decrease the volatility of your portfolio (and volatility eats away at returns.) And the higher your percentage of bonds the higher the rebalancing bonus will be when the market inevitably crashes.

What type of bonds should you hold in your portfolio?

In general the sweet spot in terms of returns and efficiency for most portfolios is medium-term bonds.

My personal philosophy is to hold predominantly short-term treasuries and short term investment-grade bond funds in my portfolio in order to avoid interest rate risk, inflation risk, and credit risk.

Of course avoiding all these risks means I am forgoing some returns.

But when the yield on long-term TIPS gets above 2 1/2 to 3% my investment policy statement calls on me to shift my bond allocation almost entirely to long term TIPS so I can lock in a real 3% return from my bond bucket for up to 30 years. (But that’s a story for another day.)

And I have no argument with holding all of your your bonds as medium-term treasuries. There is nothing wrong with that, and it may very well be smarter than my strategy.

(This increase in interest rate/inflation risk has been adequately compensated by the market in the past.) I wouldn’t even argue holding long term equities as your bonds in portfolios with high equity allocations (>90% equities.)

But I what I would not recommend is including real estate investment trusts, high-yield (junk) bonds, or P2P loans in your bond bucket. And the reason is that these assets all have equity like risk when the stock market drops which kind of defeats the purpose of having bonds in your portfolio in the first place.

* Yes I am ignoring term risk, liquidity risk, credit downgrade risk etc….

What is your bond percentage, bond allocation, and critique of my bond philosophy? (I’m 25%, short term treasury/tips/short term investment grade depending on the interest rate.)

21 Responses to “What I Talk About When I Talk About Bonds”